STEM in EUROPE: the Talent Paradox

Why are PhDs leaving research when the market has never needed them more?

While Europe faces a massive STEM talent shortage, a paradox persists: many doctoral candidates are leaving research due to lack of visibility on their career prospects. How can we explain this dropout at the very moment when scientific skills have never been so sought after?

A market in search of scientific talent

Bridges between research and industry

The era of the versatile specialist

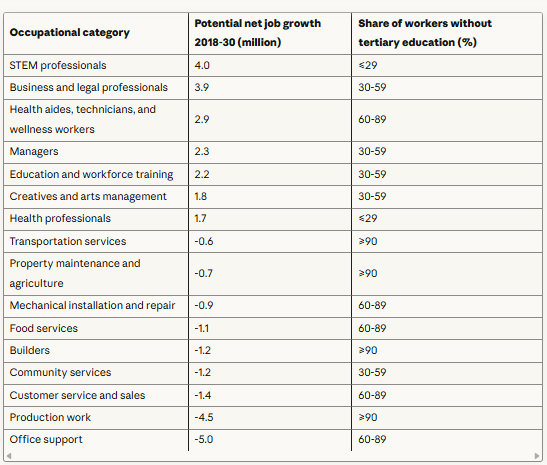

STEM – for Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics – encompasses all scientific and technical disciplines that form the foundation of European innovation. And these disciplines are facing a recruitment crisis. Europe currently lacks 2 million professionals in these fields, according to the European Commission. Professional, scientific and technical services will experience growth of 17.3% by 2030, representing 2.6 million additional jobs to fill. The illustration shows the potential net job growth for the period 2018-2030 in a midpoint automation scenario, in millions, according to statistics from McKinsey & Company.

Yet a significant number of doctoral students abandon their thesis before defending it. Among those who obtain their doctorate, many leave the scientific sector permanently. This paradox reveals a deep disconnect between doctoral training and labor market realities: STEM doctoral students, trained in scientific excellence, often lack awareness of the opportunities available to them in the private sector, where their skills are actively sought after.

Yet a significant number of doctoral students abandon their thesis before defending it. Among those who obtain their doctorate, many leave the scientific sector permanently. This paradox reveals a deep disconnect between doctoral training and labor market realities: STEM doctoral students, trained in scientific excellence, often lack awareness of the opportunities available to them in the private sector, where their skills are actively sought after.

This observation is not new. As early as the 1970s, Bernard Gregory (in the photo, he is in the middle), French physicist and former Director-General of CERN (1966-1970), already carried a revolutionary vision: that of research connected to the economic and social world. It was in this spirit that the Association bearing his name was founded in 1980. For over 40 years, ABG has demonstrated that a doctorate is not a dead end, but a springboard to diverse careers. Today, given the scale of the STEM shortage, this conviction is more relevant than ever.

But then, how can we explain that companies struggle to recruit precisely the profiles that universities are training in large numbers? The answer lies in three major challenges: a lack of awareness of real market opportunities, persistent compartmentalization between research and industry, and an evolution in employer expectations toward more versatile profiles.

A market in search of scientific talent

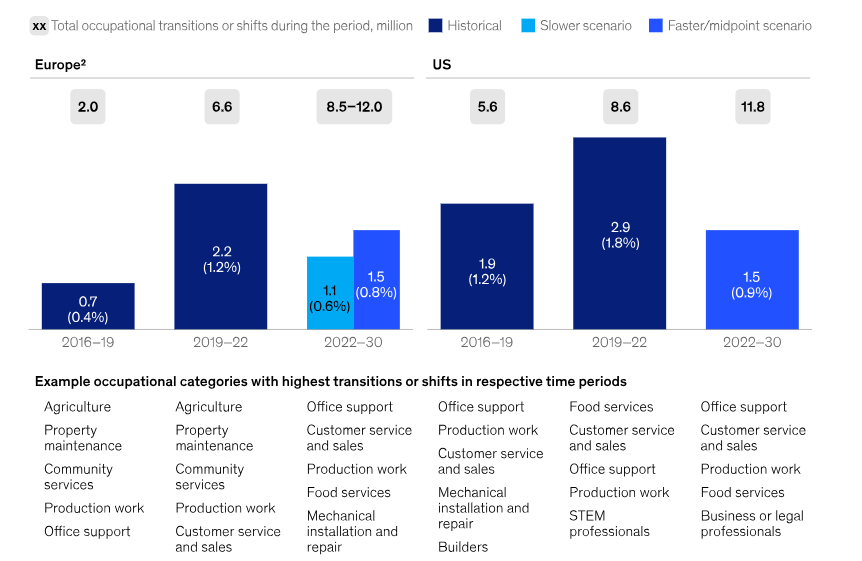

The figures speak for themselves: according to the McKinsey report "A New Future of Work" (2024), demand for STEM professionals will experience growth of 17 to 30% between 2022 and 2030. Even more striking, 80% of European SMEs report difficulty recruiting scientific and technical talent (Eurobarometer 2023).  This tension in the labor market concerns all qualification levels, but it is particularly acute for doctoral profiles. The illustration shows the net expected change in labor demand for the EU and the US in a faster/midpoint scenario 2022-2030, according to analysis by McKinsey & Company.

This tension in the labor market concerns all qualification levels, but it is particularly acute for doctoral profiles. The illustration shows the net expected change in labor demand for the EU and the US in a faster/midpoint scenario 2022-2030, according to analysis by McKinsey & Company.

This demand is concentrated in strategic sectors for Europe's future. Clean technologies, driven by the Green Deal and the goal of carbon neutrality by 2050, are creating massive demand for environmental engineers and green chemists. Artificial intelligence and quantum computing are absorbing data scientists and machine learning researchers as fast as universities can train them. Biotechnology and digital health, with projected growth of +12.9%, are seeking experts in pharmaceutical R&D and bioinformatics. As for cybersecurity, aerospace and advanced robotics, these sectors offer career prospects that few doctoral students know about.

Yet these career paths extend far beyond traditional academic research. Companies are seeking PhDs for varied functions: industrial R&D, scientific consulting, data science, innovation management, and even deep tech startup creation. This diversity of possible careers remains largely invisible to doctoral students, confined to a vision that reduces their future to an academic position or failure.

How, then, can we recreate the link between these two worlds that ignore each other? This is precisely the role of innovation ecosystems emerging in Europe.

Bridges between research and industry

Faced with this compartmentalization, new collaborative ecosystems are emerging across the continent. The STEM Alliance, for example, brings together more than 350 universities and 380 major industrial partners – Cisco, Microsoft, Intel, Airbus Foundation. This consortium has already contributed to the creation of more than 240 research-based startups, demonstrating that structured collaboration between academia and industry can bear fruit.

The European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT) moves in the same direction with its Deep Tech Talent initiative, which has trained over one million people in cutting-edge technology fields. Its nine Knowledge and Innovation Communities (KICs) channel more than 3 billion euros between 2021 and 2027 toward entrepreneurial education and industry-research collaboration.

The European Union itself is multiplying support programs. Horizon Europe has a budget of 95.5 billion euros for research and innovation. The Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions fund doctoral scholarships, research networks and personnel exchanges between sectors. The Digital Europe Programme invests 1.3 billion euros for digital skills and AI. More recently, the Choose Europe for Science initiative (500 million euros, 2025-2027) aims to attract international researchers to the continent.

These mechanisms demonstrate institutional awareness. But they will not be enough to bridge the gap between supply and demand if the profiles themselves do not evolve. Because companies are no longer just looking for technical experts – they want specialists capable of innovating outside the laboratory.

The era of the versatile specialist

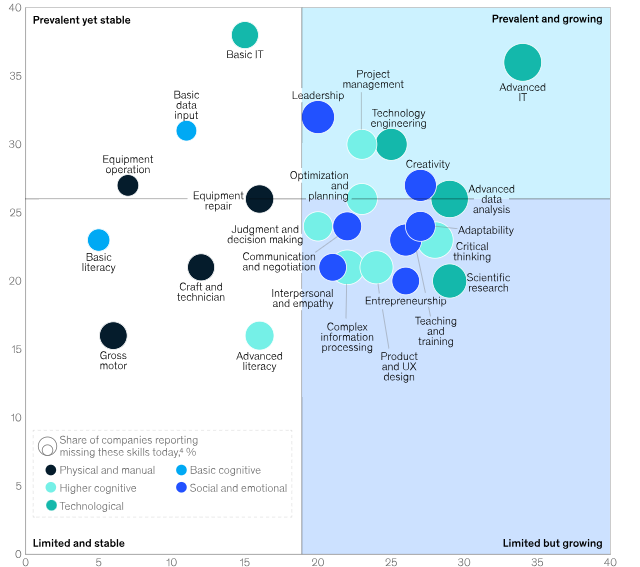

The STEM labor market has fundamentally changed. According to McKinsey, demand for social and emotional skills will increase by 11% in Europe by 2030, while demand for technological skills will grow by 25%. In other words, companies no longer want to choose between specialized expertise and cross-functional abilities – they demand both.

This evolution is an opportunity for PhDs, whose training precisely meets this dual requirement. Managing a research project over three to five years develops project management and autonomy. Publishing and presenting at international conferences forges scientific communication. Formulating hypotheses and analyzing complex data builds critical thinking and problem-solving. Collaborating with international teams brings cultural and linguistic adaptability. The illustration shows the skills of today vs skills of tomorrow in the EU and US, in %, according to predictions by McKinsey & Company.

The problem is not that PhDs lack skills – it's that they don't know how to present them in language that companies understand. They remain confined to academic jargon, unable to translate "I defended a thesis on stochastic modeling" into "I can analyze complex systems and make decisions in uncertain contexts."

In a context where 12 million professional transitions will be necessary in Europe by 2030, this ability to reposition oneself becomes crucial. The STEM PhD, trained in continuous learning and seeking innovative solutions, naturally possesses this adaptability. They just need to become aware of it – and companies need to know how to recognize it. The illustration shows the occupational shifts for the periods 2016-19 and 2019-22 as well as anticipated occupational transitions 2022-30, in slow, faster and midpoint scenarios, as yearly average, according to McKinsey & Company.

A shared responsibility

The STEM talent paradox will not resolve itself. It calls for dual awareness.

On the company side, it is time to recognize the value of the doctorate. This requires concrete actions: explicitly valuing this degree in job offers and salary scales, developing integration pathways adapted to scientific profiles, participating in academia-industry networking events like the PhDTalent Career Fair. These profiles bring depth of analysis and innovation capacity that few other training programs can provide.

On the doctoral student side, the challenge is to move beyond the niche vision of the academic researcher to adopt a strategic vision of the scientific job market. Identifying growth sectors, presenting expertise in accessible language, building a professional network that extends beyond laboratory walls: all skills that can be developed, and that ABG has been working to transmit for over 45 years.

Because this is precisely the meaning of the mission Bernard Gregory envisioned: making science a career lever, not a dead end. Our professional training programs, networking events, and personalized support all aim for the same goal – giving doctoral students the visibility and confidence necessary to fully invest in the STEM market.

STEM is Europe's future. STEM PhDs are the architects of that future.

With the right tools and a clear vision, every doctoral student can transform their expertise into a sustainable career. ABG is here to contribute to that.

Find out more

The professional situation of PhDs in France: a portrait in figures and trends

The job market for PhD graduates in France is generally very stable three years after graduation, with an employment rate exceeding 94%. However, this excellence masks disparities based on discipline, nationality, or gender, revealing persistent inequalities. Using statistical analysis from the IPDoc 2023 survey, this article examines the profiles, career paths, and challenges of PhD graduates in 2020, highlighting strengths and areas for improvement for the future of research and doctoral employment in France. Read further (in French).

DocPro: a brand new tool to connect doctorate holders and companies

Wojciech Lewandowski - Community manager

(Pour consulter cet article en français, cliquez ici)DocPro is an online platform that helps PhDs to highlight their professional and personal skills in front of employers. It may be used by PhDs from all scientific fields, from STEM to Humanities, and from all countries. The tool is available in French and English.

DocPro was developed by the Association Bernard Gregory (ABG), the French Conference of University Presidents (CPU) and the French Business Confederation (MEDEF).

The aim was to have companies, doctorate holders and doctoral programmes managers share the same understanding of the skills a doctorate develops.

Get ABG’s monthly newsletters including news, job offers, grants & fellowships and a selection of relevant events…

Discover our members

Aérocentre, Pôle d'excellence régional

Aérocentre, Pôle d'excellence régional  CASDEN

CASDEN  CESI

CESI  Généthon

Généthon  Nokia Bell Labs France

Nokia Bell Labs France  MabDesign

MabDesign  Groupe AFNOR - Association française de normalisation

Groupe AFNOR - Association française de normalisation  MabDesign

MabDesign  TotalEnergies

TotalEnergies  ONERA - The French Aerospace Lab

ONERA - The French Aerospace Lab  PhDOOC

PhDOOC  Laboratoire National de Métrologie et d'Essais - LNE

Laboratoire National de Métrologie et d'Essais - LNE  Ifremer

Ifremer  SUEZ

SUEZ  ASNR - Autorité de sûreté nucléaire et de radioprotection - Siège

ASNR - Autorité de sûreté nucléaire et de radioprotection - Siège  ADEME

ADEME  Tecknowmetrix

Tecknowmetrix  ANRT

ANRT  Institut Sup'biotech de Paris

Institut Sup'biotech de Paris